I am pleased to announce the launch of a brand new blog that I am a part of. Four Aberdeen systematic theology PhD students, myself, Jon Coutts, Justin Stratis and Darren Sumner will be contributing to Out of Bounds: Theology in the Far Country, a blog seeking to generate healthy and probing theological conversations. Jon Coutts has written a fantastic opening post articulating the kind of "gospel conversation" we are seeking to foster. Check it out!

This new blog will now be my primary blogging home. Draw Nigh will still be here, but will remain basically inactive for the immediate future.

Monday, June 27, 2011

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Transitions

Though nothing has been going on here at Draw Nigh for several months, quite a bit has been going on for me and its time I post an update. First, my family and I have moved from Aberdeen, Scotland back to our dear old Santa Cruz, Ca. It was crazy trying to get all our stuff between countries, especially since I came back with WAY more books than I went with. It was also very bittersweet as we knew we were coming back to so many friends and family we love in Santa Cruz, but were also leaving friends we love that had become our family in Aberdeen.

Though nothing has been going on here at Draw Nigh for several months, quite a bit has been going on for me and its time I post an update. First, my family and I have moved from Aberdeen, Scotland back to our dear old Santa Cruz, Ca. It was crazy trying to get all our stuff between countries, especially since I came back with WAY more books than I went with. It was also very bittersweet as we knew we were coming back to so many friends and family we love in Santa Cruz, but were also leaving friends we love that had become our family in Aberdeen.Now settled back in, I'll be splitting my time here between finishing my dissertation and working in ministry at Twin Lakes Church in Aptos, Ca., the church I grew up in and love as my family.

As for blogging activity, I'm working on a group blog with some friends and fellow theo-bloggers from Aberdeen which will hopefully be launching this week.

I'm also working on a personal web site which will just be a place to host my CV online and post updates about conferences and publications I'll be a part of.

As for Draw Nigh, it has been close to totally inactive for several months and will likely remain that way for a while, but I'm hoping to come back to it before to long. My hope is to use it as a forum to extend conversations taking place in my church ministry, discussing biblical and theological questions coming from Christians without much or any academic theological training and seeking to address those questions without technical jargon - a theology blog for the Christian layperson if you will.

Updates will be coming!

Friday, April 8, 2011

Evangelical Calvinism Book

Here is what the table of contents to the Evangelical Calvinism book will look like. I just submitted the final final draft yesterday for my chapter, which is entitled "The Depth Dimension of Scripture: A Prolegomenon to Evangelical Calvinism", and am pretty excited about it. They are looking for a release date late 2011/early 2012. Be on the lookout!

Thursday, March 24, 2011

Original Autographs

So, I've been thinking. As a person who desires to make a living pastoring and teaching in the Evangelical world, I might be incredibly stupid to bring this up, but I don't like statements of faith that talk about the Bible being inspired "in the original autographs". So many churches and educational institutions have this line in their doctrinal statements, often as the first line of it. This doesn't sit right with me.

What don't I like about it? Well, I'll tell you.

First, the historical reality of something called an "original autograph" is entirely doubtable for many books of the Bible. What was the "original" version of the Psalms? Does "original autograph" refer to the first written version of each independent Psalm? The first time a collection of Psalms were brought together? The collection as we now have it in our Bibles? Statements which limit the scope of inspiration to original autographs show a lack of appreciation for the processes involved in bringing much of the Old Testament into the form we have it. Why limit the Spirit's inspiring work to a particular stage in the life of a text's production, especially when a term like 'original autograph' is so ill suited to specify which stage we have in mind?

Second, more importantly, and more in line with what Evangelicals really care about, explicitly limiting the inspiration of Scripture to a supposed "original autograph" calls into question the authority of Scripture as it is present in the church today. It makes Scripture's authority in the church today definitively dependent on the human work of text criticism rather than the divine work of the Holy Spirit. Our confessions need to be statements of faith in God in his work of revelation and reconciliation, while of course including his use of creaturely media to accomplish his will, among which Scripture is essential. That is to say, our confessions need to be biblical! Scripture speaks of no such things as original autographs, so why make them an object of confession? (If you say, "the Bible doesn't have the word 'Trinity' in it either", I'll seriously punch you.) New Testament writers appeal to the Old Testament as authoritative without ever grounding those appeals on a distinction between original autographs and anything else. In fact, they freely cite the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew Old Testament into Greek, obviously not original autographs, yet there is no qualifying of its authority. Likewise, if we are to confess the inspiration of Scripture, which we certainly must do, we need to define that inspiration in terms broad enough to see the Spirit's work include the whole range of processes by which the books of Scripture were composed, redacted, collected, and preserved through the ages. (Actually, we first need to see the composition of the biblical books in coordination with the redemptive acts God has done in the foundation and life of Israel and the church in which Scripture has its authority and is to be interpreted).

The questions brought up by the admission of stages of composition or redaction, questions such as "if there were several versions of a book along the way, which version is God's Word", make the mistake of thinking of divine revelation entirely in terms of the verbal form of Scripture rather than in terms of the living God continually speaking of himself through those verbal forms by his Spirit. In other words, anxiety over such questions manifests a view of the Spirit's work in history so narrow and punctiliar as to be nearly deistic. If the Spirit doesn't speak now through Scripture as he spoke through it as it was first received, then it is of no use to us. If he does speak now through it, then our statements of faith out to reflect such a trust in Scripture in the unity of its original reception (if it even makes sense to speak of such a thing) and its present reception.

That being said, I am still willing to sign statements containing language about original autographs. It is not that I hold suspicion about the inspiredness of Scripture in any earlier version than we have now, its just that I see no reason not just say that we believe Scripture to be inspired and authoritative for Christian thinking and living. I see no benefit gained by the inclusion of "in the original autographs", only problems. Am I missing something?

What don't I like about it? Well, I'll tell you.

|

| I'm pretty sure this is what people mean by "original autograph". |

Second, more importantly, and more in line with what Evangelicals really care about, explicitly limiting the inspiration of Scripture to a supposed "original autograph" calls into question the authority of Scripture as it is present in the church today. It makes Scripture's authority in the church today definitively dependent on the human work of text criticism rather than the divine work of the Holy Spirit. Our confessions need to be statements of faith in God in his work of revelation and reconciliation, while of course including his use of creaturely media to accomplish his will, among which Scripture is essential. That is to say, our confessions need to be biblical! Scripture speaks of no such things as original autographs, so why make them an object of confession? (If you say, "the Bible doesn't have the word 'Trinity' in it either", I'll seriously punch you.) New Testament writers appeal to the Old Testament as authoritative without ever grounding those appeals on a distinction between original autographs and anything else. In fact, they freely cite the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew Old Testament into Greek, obviously not original autographs, yet there is no qualifying of its authority. Likewise, if we are to confess the inspiration of Scripture, which we certainly must do, we need to define that inspiration in terms broad enough to see the Spirit's work include the whole range of processes by which the books of Scripture were composed, redacted, collected, and preserved through the ages. (Actually, we first need to see the composition of the biblical books in coordination with the redemptive acts God has done in the foundation and life of Israel and the church in which Scripture has its authority and is to be interpreted).

The questions brought up by the admission of stages of composition or redaction, questions such as "if there were several versions of a book along the way, which version is God's Word", make the mistake of thinking of divine revelation entirely in terms of the verbal form of Scripture rather than in terms of the living God continually speaking of himself through those verbal forms by his Spirit. In other words, anxiety over such questions manifests a view of the Spirit's work in history so narrow and punctiliar as to be nearly deistic. If the Spirit doesn't speak now through Scripture as he spoke through it as it was first received, then it is of no use to us. If he does speak now through it, then our statements of faith out to reflect such a trust in Scripture in the unity of its original reception (if it even makes sense to speak of such a thing) and its present reception.

That being said, I am still willing to sign statements containing language about original autographs. It is not that I hold suspicion about the inspiredness of Scripture in any earlier version than we have now, its just that I see no reason not just say that we believe Scripture to be inspired and authoritative for Christian thinking and living. I see no benefit gained by the inclusion of "in the original autographs", only problems. Am I missing something?

Saturday, March 19, 2011

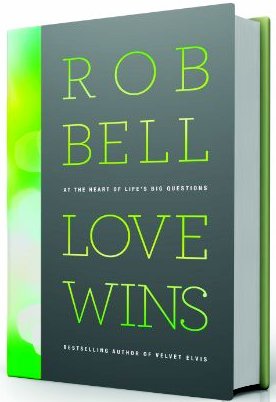

Some Worthwhile Rob Bell Reviews

Updated: 6:51 pm GMT, 3/19/2011

Well, if you follow this blog you'll notice I've tried to step back from all the hoopla surrounding Rob Bell's recently released church bonfire fuel, Love Wins. But try to avoid it as I may, the onslaught of ridiculous things said about it on the web and the thoughtful things my friends in Aberdeen have said about it, especially since a few of them have now actually read it, has brought me to order it for myself: it'll be here on Tuesday and I'll read it by next weekend - expect some thoughts to follow, if I have any. In the meantime, I've also been encouraged that some thoughtful and respectful reviews have finally started to appear.

- Fuller President Richard Mouw has a good one here.

- Steve Holmes, senior lecturer in systematic theology at the U. of St. Andrews, has a great review series of it . So far there are three parts:

- Part 1, arguing that though the book is flawed, it is nonetheless important and worth reading for its suggestions that what is wrong with what many Christians have been taught about salvation and life-after-death brings with it a quite unbiblical view of who God is, also that Bell is unambiguously not a Universalist.

- Part 2, arguing that virtually all the pillars of Reformed Orthodoxy (Edwards, Hodge, Warfield, etc.) support Bell's contention that there will be vastly more people in heaven than in hell, though this is one of the most attacked claims in the book.

- Part 3, arguing that Bell has taken an unfortunately reverted to the use of loaded questions, caricature, otherwise less than gracious tactics in this book, unlike his previous books. This entry seems a bit cut off, like he was in the middle of developing a larger point and accidentally hit the "publish" button.

- David Congdon has done an expansive (over 13,000 words!) response to a review of Bell's book by Mark Galli, senior managing editor of Christianity Today. The review is broken into five parts; an index can be found here. I've just begun reading this one myself; the stated intent is to challenge Galli's characterization of Bell as a liberal in opposition to orthodox Evangelicalism.

- Finally, though Bell doesn't call himself a Universalist, Robin Parry calls himself one and has a helpful article in the Baptist Times making clear what Christian Universalism is and what it isn't.

Friday, March 18, 2011

Is Theology Totally Irrelevant to the Church Today?

John Webster's editorial in the new issue of IJST has me a bit depressed. In it he discusses the conditions in which theological intelligence is most likely to thrive. His first point is that it is likely to flourish when it understands its vocation as "contemplative and apostolic", contemplative in that addresses itself to the deep things of God and apostolic because it commends these things to others - no problem there. Second, the whole enterprise of Christian theology is enhanced when it attracts godly and intellectually gifted people to its pursuit - no problem there either.

John Webster's editorial in the new issue of IJST has me a bit depressed. In it he discusses the conditions in which theological intelligence is most likely to thrive. His first point is that it is likely to flourish when it understands its vocation as "contemplative and apostolic", contemplative in that addresses itself to the deep things of God and apostolic because it commends these things to others - no problem there. Second, the whole enterprise of Christian theology is enhanced when it attracts godly and intellectually gifted people to its pursuit - no problem there either.Its in points three and four I get bummed out.

Third, Christian theology flourishes when in some measure it enjoys favourableThose of us who have made the sacrifice to leave our normal lives and go to a theological school are blessed (if it is a good school) to temporarily live in a situation that satisfies this condition. I can attest that in Aberdeen we are abundantly blessed with a situation in which academic, spiritual and social life intertwine in an almost Edenic situation for theological pursuit. We read and think and write and talk (some of us even pray) all the live-long day. Those who have gone through this training for the spiritual life of the mind/intellectual life of the spirit and have returned to the real world have made, as Webster notes, "little apparent impact", no sales-record-breaking books, no mega-church ministries. Usually guys like us go into rather humble academic teaching or church ministry jobs. The question is whether we will be able to foster similar intellectual situations when we leave the academy and go back into the real world. Those of us who get university jobs won't have this problem, but those of us who go back to our homes and churches have this question in front of us: Will the insights we have gained and the patterns of reflection we have developed in our theological study benefit the life of the church for whom we toil, or will it all be filtered through ears who only hear the potential for church growth or other practical impact. This leads Webster's fourth point:

institutional circumstances: some particular academic or religious form of life which

is hospitable to a work of the mind with little apparent impact, some happy gathering

of minds with sufficient rapport and energy that their unique talents combine to form

something like a school. (Webster, "Editorial", International Journal of Systematic Theology, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 128)

Fourth, Christian theology flourishes when it honours and is held in honour by the Christian community. Theology is ecclesial science, a work of reason pursued (whatever its precise institutional locale) within the community of election and faith. All its inquiries ought to hold that community in high esteem, as a servant glad to be about its tasks in such a company; and that company, too, should esteem this servant and expect good things of its service. ("Editorial", p. 128)I've already alluded to my worry here: will the churches us theologians go to and serve, either as pastors or even on a volunteer lay level, welcome us as theologians, value our training and insights, be willing to hear and consider the sometimes difficult things we have to tell the church? Have Evangelical churches in America become so focused on the tangible (cars in the parking lot, butts in the pews, hands in the air, testimony of changed lives - all good things by the way) that it simply does not value the other kinds of good things theologians' service has to offer? Most of us love the church and want to serve it; the worry is that it doesn't love us and doesn't want our service.

Webster (who I should probably mention is my doctoral advisor, not that I otherwise wouldn't think he is right about everything, which he is), does go on to alleviate my depression in his fifth point which is that we get it wrong when we think these conditions are in fundamentally worse shape now than they were at some other point in history - "Theology is not exiled from its past but its future." The present is not depressing in light of the past but in light of the future in which sin is removed as an obstacle and theology is fully united to He whom it considers. The fifth condition is that we believe theology is actually possible, that in spite of the limitations imposed on us in our currently fallen context, we believe that "God is not hindered by our hindrances", that God speaks and enables us to hear and understand. On that basis, no matter what intellectual climate I find myself in in the future, I will pray with Habakkuk "I stand in awe of your deeds, O LORD. Renew them in our day, in our time make them known" (Hab 3:2), not that God would restore some notion of the past but that he would reach into the present from the future and give the church a love for himself and for thinking on the gospel greater than its present love for spectacle and novelty in his name. I pray this against my own fears that I make myself increasingly irrelevant to the church by pursuing disciplined thinking on the church's foundation.

(To get more people to be directed to this post from Google: Rob Bell, Hell, Universalism, Sex, Money, Murder - thank you).

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

Church and Gospel: Which determines which?

Reading the first pages of prolegomena in Robert Jensen's Systematic Theology is refreshingly brisk and painless work. In situating the task of systematic theology within the self-understanding of the church, he gives a simple account of the church as the community formed by the expansion of the gospel from those who directly witnessed the risen Christ and who both recognized the universal import of what they witnessed and moreover were directly told by Christ to go and tell the nations, to the progressive expansion of people hearing that message and thereby becoming proclaimers of it to new hearers.

But fairly quickly he makes what I think is a problematic move:

Of course, if in reaction to this we decide that gospel and church must be conceived so that the gospel is entirely free vis-a-vis the church, able to promote itself through other means just as easily as through the church, then we would have to hold out the possibility of multiple churches, multiple communities that the gospel calls into being with no underlying unity obligating them to work toward making that unity visible.

It would seem that the solution is to hold gospel and church inseparably together but in a consistently ordered way so that the gospel is the determinant of the church and not the other way around. What the gospel is is the message of Jesus Christ through which the Holy Spirit gathers a people together for God, while the church is the Spirit's servant chosen to continue that message, but always under a unilateral conditioning by the message, not mutually conditioning it. The gospel and the Church are bound together in inseparable unity, but as a unity of master and servant, not substance and container. The master has chosen this servant and carries out his work uniquely through this servant's service, but this service is always freely chosen by the master. Conceived as a relation of substance and container, we would have to say that though it is the value of the substance that determines the need and worth of the container, the container is what actually gives shape to the substance. However, conceived as master and servant, it is the master's command that determines the servants's service; the servant's service does not determine the master's command.

But fairly quickly he makes what I think is a problematic move:

Is this right? Does the church determine the gospel in the same way or even to the same degree that the gospel determines the church? To say yes would seem to lead to all kinds of problems, most obviously the problem that since the church is a continuous community and therefore a community spanning generations, centuries, and even millennia of cultural change, as the church inescapably changes with the times we would have to say that the gospel itself changes.It is the historically continuous community, which in this way began and perdures, that her own linguistic custom calls "the church." "Church" and "gospel" therefore mutually determine each other. Whether we are to say that God uses the gospel to gather the church for himself, or that God provides the church to carry the gospel to the world, depends entirely on the direction of thought in a context. (Jensen, Systematic Theology, vol. 1, pp. 4-5).

Of course, if in reaction to this we decide that gospel and church must be conceived so that the gospel is entirely free vis-a-vis the church, able to promote itself through other means just as easily as through the church, then we would have to hold out the possibility of multiple churches, multiple communities that the gospel calls into being with no underlying unity obligating them to work toward making that unity visible.

It would seem that the solution is to hold gospel and church inseparably together but in a consistently ordered way so that the gospel is the determinant of the church and not the other way around. What the gospel is is the message of Jesus Christ through which the Holy Spirit gathers a people together for God, while the church is the Spirit's servant chosen to continue that message, but always under a unilateral conditioning by the message, not mutually conditioning it. The gospel and the Church are bound together in inseparable unity, but as a unity of master and servant, not substance and container. The master has chosen this servant and carries out his work uniquely through this servant's service, but this service is always freely chosen by the master. Conceived as a relation of substance and container, we would have to say that though it is the value of the substance that determines the need and worth of the container, the container is what actually gives shape to the substance. However, conceived as master and servant, it is the master's command that determines the servants's service; the servant's service does not determine the master's command.

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

A Damaging Ambiguity in Modern Worship

After living in Scotland for about a year and a third, attending a Church of Scotland church where the worship music is primarily hymns and an organ, I spent most of December and January back home in Santa Cruz, Ca. It was great in those months to be back at my home church where my wife and I both grew up and have tons of friends and family, but something I had struggled with for years in the kind of modern worship we do at our home church was brought fresh to my mind in its contrast with more traditional hymnody. (Generalization alert: just go with it). Hymns are focused on who God is, what he has done, asserting the worshippers' faith in him and asking for God's blessings in faith. Modern worship is primarily concerned with the worshipper's (notice the different placement of the apostrophe) subjective response to God's being, presence and/or blessings. Where hymns sing things like...

After living in Scotland for about a year and a third, attending a Church of Scotland church where the worship music is primarily hymns and an organ, I spent most of December and January back home in Santa Cruz, Ca. It was great in those months to be back at my home church where my wife and I both grew up and have tons of friends and family, but something I had struggled with for years in the kind of modern worship we do at our home church was brought fresh to my mind in its contrast with more traditional hymnody. (Generalization alert: just go with it). Hymns are focused on who God is, what he has done, asserting the worshippers' faith in him and asking for God's blessings in faith. Modern worship is primarily concerned with the worshipper's (notice the different placement of the apostrophe) subjective response to God's being, presence and/or blessings. Where hymns sing things like...See from His head, His hands, His feet, Sorrow and love flow mingled down! Did e’er such love and sorrow meet, Or thorns compose so rich a crown?

Modern worship sings things like...

The fullness of Your grace is here with me, The richness of Your beauty’s all I see, The brightness of Your glory has arrived, In Your presence God, I’m completely satisfiedThere is an important difference here that I think causes a significant amount of spiritual anguish for many who participate in modern worship. The modern worship song is describing a state of mind that the worshipper is claiming for him/herself, one in which God's beauty is all they see so that they are completely satisfied. How does one sing that if what they actually see is the ugliness engulfing their lives leaving them anything but satisfied? A spiritual pressure is put on the worshipper to feel that way, to manipulate their own psychology to conform to that feeling. Some do. Some are somehow able to play that part with relative ease. I won't speak to their own spiritual situation because I simply can't relate to it, but I usually suspect that they are forcefully hiding something from themselves - I realize, however, that it really isn't my place to judge. Others are faced with a crisis. They are led to the conclusion that this kind of elevated feeling is what faith looks like, and they either need to drum up some good vibrations or deal with the fact that they might just not be capable of faith.

Notice how the hymn doesn't demand that kind of psychological conformity. It calls the worshipper to think about the gospel, not to feel a certain way but simply to recognize it. It is speaks of the grace, beauty and glory of God's presence in the creaturely realm and even elicits an emotional subjective response, at least from me, but the hymn isn't about that subjective response, it occasions it. The modern worship song is actually about the subjective response; one gets the sense that the feeling is the actual intent or object of the song.

There is a theological ambiguity at play here that I want to address. As biblical as it is to speak of the faithfulness of God and the satisfaction that comes in receiving it, we must pay constant attention to the lingering effects of sin. That we worship God as sinners means that his beauty will never be all we see until our redemption is made complete when Christ returns. We will never be completely satisfied in God's presence this side of Christ's return because we are not yet in his presence free of the entanglements of sin. We are in his presence in Christ and his presence is in us by the Spirit, but that reality is hidden with Christ in God for the present, the Spirit being present in us as the promise that we will one day be satisfied.

These thoughts have been brought to mind for me as I have been reading Karl Barth's commentary on Paul's Epistle to the Romans, a troubling book in many ways but nonetheless filled with theological insight. Speaking to my frustration over modern worship, Barth has this to say about people's assumption of experiencing God:

Later, he quotes Calvin:Whenever men suppose themselves conscious of the emotion of nearness to God, whenever they speak and write of divine things, whenever sermon-making and temple-building are thought of as an ultimate human occupation, whenever men are aware of divine appointment and of being entrusted with a divine mission, sin veritably abounds - unless the miracle of forgiveness accompanies such activity; unless, that is to say, the fear of the Lord maintains the distance by which God is separated from men.

Everything by which we are surrounded conflicts with the promise of God. He promises us immortality, but we are encompassed with mortality and corruption. He pronounces that we are righteous in His sight, but we are engulfed in sin. He declares His favour and goodwill towards us, but we are threatened by the tokens of his wrath. What can we do? It is His will that we should shut our eyes to what we are and have, in order that nothing may impede or even check our faith in Him.

Calvin's call to place our faith in what we hear in the gospel rather than what we see in our experience brilliantly captures the heart of the gospel. If we are consciously aware that we are intentionally negating our experience of seeing ugliness and being unsatisfied in faith, then I think we can joyfully sing the modern worship song (though we'd still probably favor the hymn). I can sing it not as a description of how I feel, but as a statement of faith, faith in the reality of the new creation I am in Christ, the one that really does only see God's beauty and really is satisfied in God's presence. The problem is that I don't see modern worship services making this contradiction clear; I see them feeding the confusion, making the worshipper think that it is their job to drum up the feelings rather than having faith in the promise despite their feelings and perception.

Calvin's call to place our faith in what we hear in the gospel rather than what we see in our experience brilliantly captures the heart of the gospel. If we are consciously aware that we are intentionally negating our experience of seeing ugliness and being unsatisfied in faith, then I think we can joyfully sing the modern worship song (though we'd still probably favor the hymn). I can sing it not as a description of how I feel, but as a statement of faith, faith in the reality of the new creation I am in Christ, the one that really does only see God's beauty and really is satisfied in God's presence. The problem is that I don't see modern worship services making this contradiction clear; I see them feeding the confusion, making the worshipper think that it is their job to drum up the feelings rather than having faith in the promise despite their feelings and perception. The answer? I don't know, but I think getting more people in leadership in modern worship churches to read Barth couldn't hurt. Keeping the dialectic of God's faithfulness and our faithlessness as a more explicit theme in modern worship would be helpful as well. Your thoughts?

Tuesday, March 8, 2011

Colloquium on Theological Interpretation in NZ

Anyone living in or able to get to NZ this summer interested in theological interpretation of Scripture should attend this colloquium.

Colloquium on Theological Interpretation

Vaughan Park, Long Bay, Auckland, New Zealand, 19-20 August 2011

Announcement and Call for Papers

Sponsored by Laidlaw-Carey Graduate School, Auckland, New Zealand and the Department of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Featuring Joel Green and Murray Rae as keynote speakers and respondents, two scholars who have been prominent in the development of theological interpretation as a discipline:

Associate Professor Murray Rae is head of the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Otago. He has been involved in a number of initiatives concerned with the theological interpretation of Scripture, including the Scripture and Hermeneutics Seminar and the Journal of Theological Interpretation. He is a member of the editorial board of the JTI and is series editor of the JTI monograph series. He is also the chair of an International Colloquium on theology and the Built Environment and has continuing research interests in the work of Søren Kierkegaard, Biblical Hermeneutics, Christian Doctrine, and the development of Christian faith amongst Maori. | |

Professor Joel B. Green is Professor of New Testament Interpretation and Associate Dean for the Center for Advanced Theological Studies at Fuller Theological Seminary. He holds the Ph.D. in New Testament Studies from the University of Aberdeen (Scotland), as well as the M.Th. (Perkins School of Theology) and the B.S. (Texas Tech University). He has completed further graduate work in the neurosciences at the University of Kentucky. In the academic world of biblical scholarship, Professor Green is noted above all for his contribution to the theological interpretation of Christian Scripture, his work in Luke-Acts, and his commitment to interdisciplinarity. In the world of the church, he is known for wearing his scholarship lightly, for his concern with the mission of the church in the twenty-first century, and for his commitment to renewal. |

Papers

This colloquium will explore the theory and practice of the theological interpretation of Scripture. The contributions by our two key note speaker / respondents will be supplemented by papers from scholars in New Zealand, Australia and the Pacific and from further afield. Potential papers might cover, but are not limited to, the following types of areas:

· Theological interpretation of particular texts.

· Issues relating to the practice of theological interpretation.

· Questions of method and theological interpretation.

· The history and landscape of the theological interpretation as a discipline.

· Cross cultural reflections on theological interpretation.

· Contemporary social, cultural and political reflections from a perspective of theological interpretation of Scripture.

· Theological interpretation, church and mission.

Papers should be designed to take 30-35 minutes to deliver with 10-15 minutes for discussion following. Abstracts of papers should be submitted no later than 31 March 2011, and should be sent to Tim Meadowcroft: tmeadowcroft@laidlaw.ac.nz. Our intention is to publish a book of essays on theological interpretation based on the offerings at the colloquium.

Attendance

There will be a fee of $50 for the colloquium (no charge for students enrolled in R133 for Friday, $15 for Saturday), with an additional $60 per night for accommodation if you wish to stay at Vaughan Park. If you would like to attend this event please register your interest via email to christina.partridge@laidlaw.

Vaughan Park Anglican Retreat and Conference Centre is a place of hospitality, conversation, theological encounter and refreshment at Long Bay on Auckland’s North Shore

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)