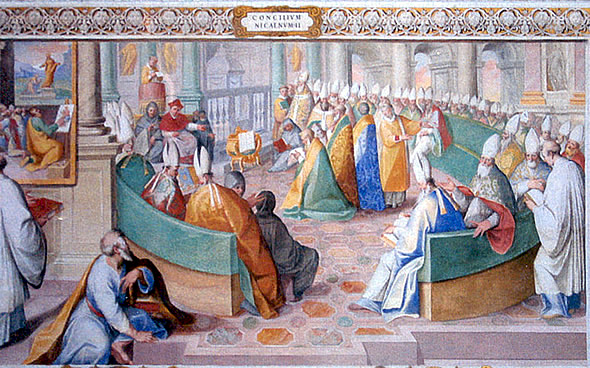

Reading Torrance's article "The Deposit of Faith" this week put a thought in my head about church doctrinal statements. Among a few other things Torrance is doing in this essay, one of them is to contrast the early ecumenical doctrinal statements, particularly the Nicene Creed, with those of the scholastic Reformed tradition, particularly the Westminster Confession. The key difference he wants to draw is that the Nicene Creed in its brevity is meant for worship - it is not primarily intended to give precise definition to the nature of God in any of his three persons or the relations between them, but to humbly and worshipfully point to the reality of the triune God in a way which both acknowledges the basic ineffability of that reality but also explicitly rules out the heresy of those such as the Arians who insist on interpreting biblical statements in mythological and anthropomorphic terms. On the other hand, the Westminster Confession and others like it with their far more cumbersome length in attempt to give precise articulation to every matter of the Reformed faith, are, in Torrance's words, "of more use to the lecture hall than the Church", being "essentially constitutional documents rather than declarations of faith before God." His point seems to be that while both share the concern to guard against heresy in these statements, Nicaea approaches this task in the form of a statement of faith meant to be used in corporate worship, carefully but humbly and transparently (in the sense of pointing to a truth it cannot fully express or contain) professing belief in the one triune God of the Bible, while Westminster seeks to exhaust the truth content of the Gospel through precise and extended formulations of doctrine which contain that truth in themselves.

Reading Torrance's article "The Deposit of Faith" this week put a thought in my head about church doctrinal statements. Among a few other things Torrance is doing in this essay, one of them is to contrast the early ecumenical doctrinal statements, particularly the Nicene Creed, with those of the scholastic Reformed tradition, particularly the Westminster Confession. The key difference he wants to draw is that the Nicene Creed in its brevity is meant for worship - it is not primarily intended to give precise definition to the nature of God in any of his three persons or the relations between them, but to humbly and worshipfully point to the reality of the triune God in a way which both acknowledges the basic ineffability of that reality but also explicitly rules out the heresy of those such as the Arians who insist on interpreting biblical statements in mythological and anthropomorphic terms. On the other hand, the Westminster Confession and others like it with their far more cumbersome length in attempt to give precise articulation to every matter of the Reformed faith, are, in Torrance's words, "of more use to the lecture hall than the Church", being "essentially constitutional documents rather than declarations of faith before God." His point seems to be that while both share the concern to guard against heresy in these statements, Nicaea approaches this task in the form of a statement of faith meant to be used in corporate worship, carefully but humbly and transparently (in the sense of pointing to a truth it cannot fully express or contain) professing belief in the one triune God of the Bible, while Westminster seeks to exhaust the truth content of the Gospel through precise and extended formulations of doctrine which contain that truth in themselves. Now, whether Torrance is right in this charge is certainly up for debate. What I'm interested in at this point is using this discussion as a springboard to ask: What are we doing with our church doctrinal statements? I am convinced that it is a good idea for each church to have them, and I come from a church tradition that is prone to keep them fairly short, which I think is a good idea. My sense is, though, that the only real reason we have them, or at least the only real way we use them (apart from having applicants sign them) is to give prospective visitors a way to see if we are heretics. This isn't a bad thing, but the concern I have is how much we separate this aspect (doctrine) from worship. The Apostles' and Nicene Creeds are such great examples of celebratory doctrine, or if you like, propositional worship. Given the absolutely theologically destitute state of most of our modern worship, it seems like a great idea to bring these kinds of (or perhaps precisely these) statements of faith back into the life of the church, poetically and theologically rich statements of faith that we don't merely post on our church websites or keep copies of behind the secretaries desk in the church office, but adopt or craft with the explicit intention of use in corporate worship (and of course we can throw them up on the website too). Those reading this that come from a liturgical background are probably saying "duh!", but I'm hoping those that come from backgrounds like mine which were built on a negative reaction against the bells and smells of high church liturgy will recognize our need to take greater pains in centering our worship more explicitly around the God and Gospel of Scripture. I'm not sure singing "Jesus I am so in love with you" is helpful by itself either in guarding against heresy or even in specifically drawing our minds to the Jesus of the Gospels rather than the Jesus of our psychology.